Unique Info About Why Is Friction Not A Force

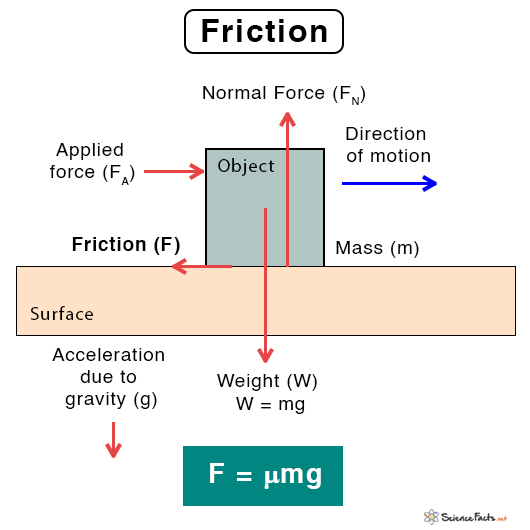

Friction is a force that resists movement between surfaces in contact.

Unraveling the Misconception: Why Friction Isn't a Force, But a Reaction

Understanding the Fundamental Nature of Interaction

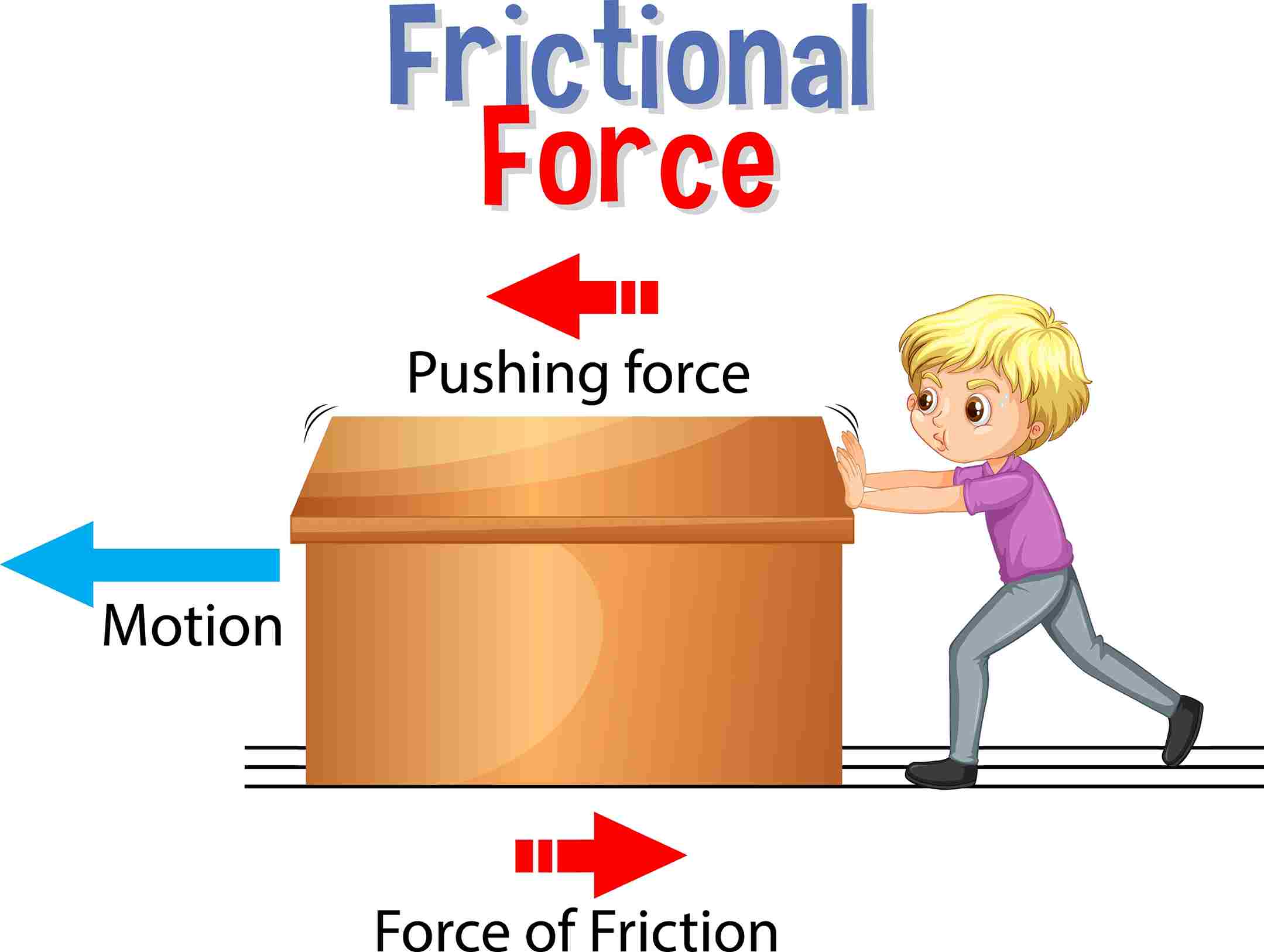

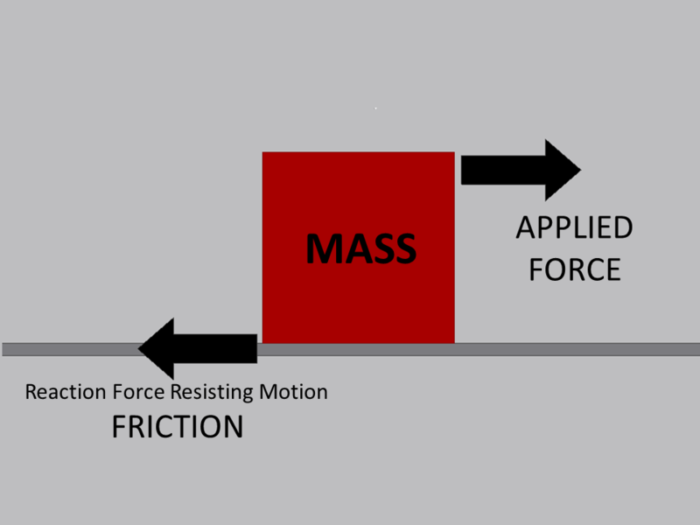

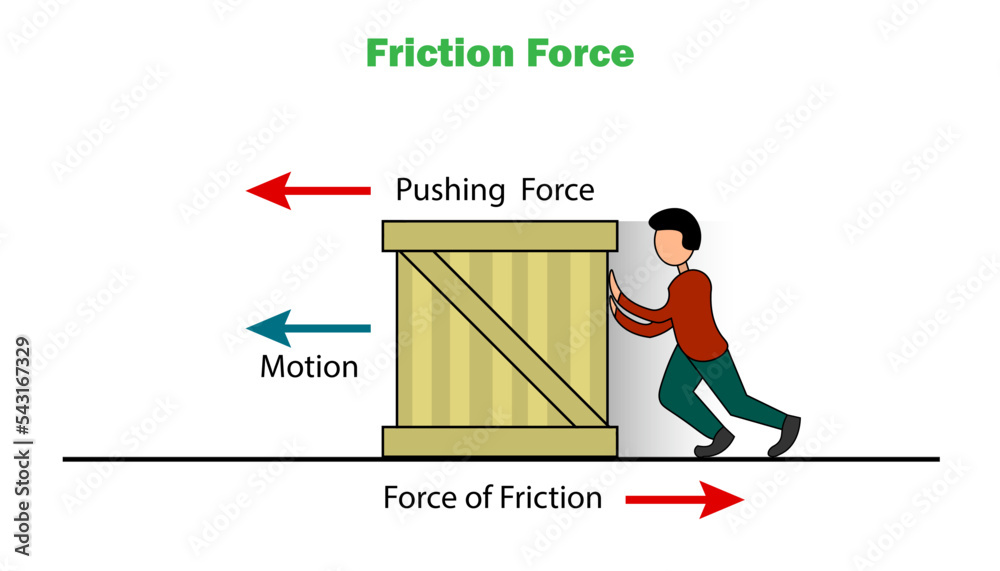

In the realm of physics, a common misconception persists: that friction is a force. While it undeniably influences motion, classifying it as a fundamental force is inaccurate. Instead, friction is more accurately described as a reactionary force, a response to applied forces rather than an independent entity. Think of it like this: when you push a box across a floor, friction resists that motion, but it wouldn't exist if you hadn't initiated the push in the first place. It's the floor's way of saying, "Hold on, not so fast!"

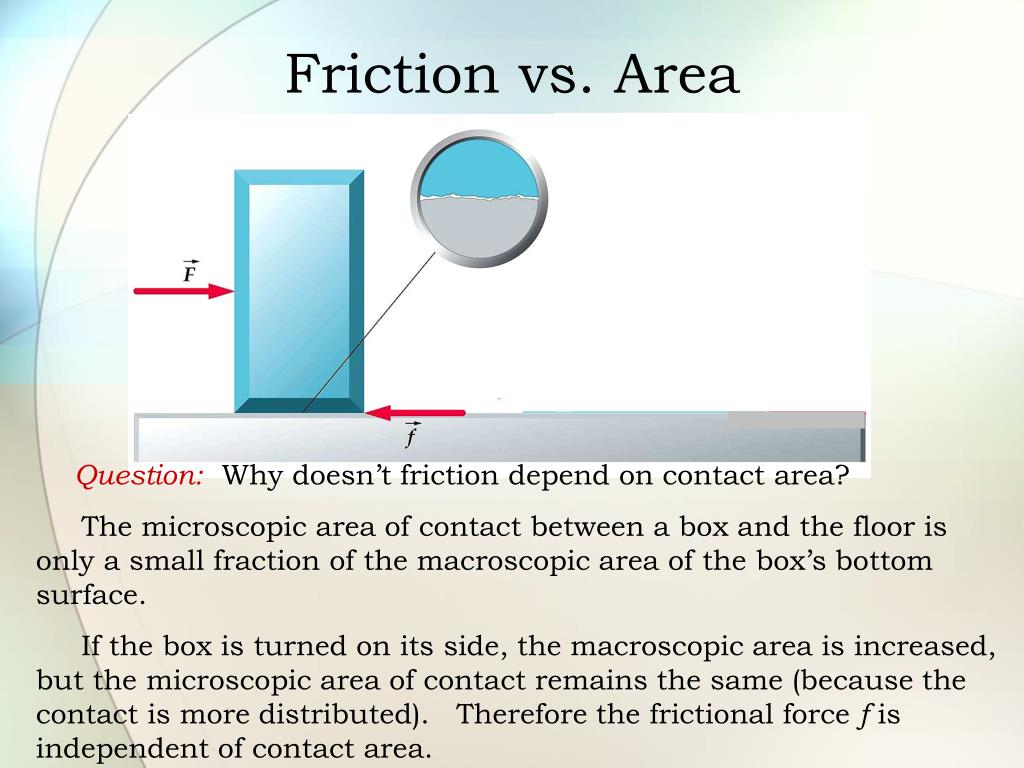

The distinction lies in the origin of the interaction. Fundamental forces, such as gravity or electromagnetism, exist independently and operate on a fundamental level. Friction, conversely, arises from the interaction between surfaces at a microscopic level. It's the culmination of countless tiny interactions between atoms and molecules, a complex dance of electromagnetic forces at play. This intricate interaction is what gives rise to the macroscopic effect we perceive as friction.

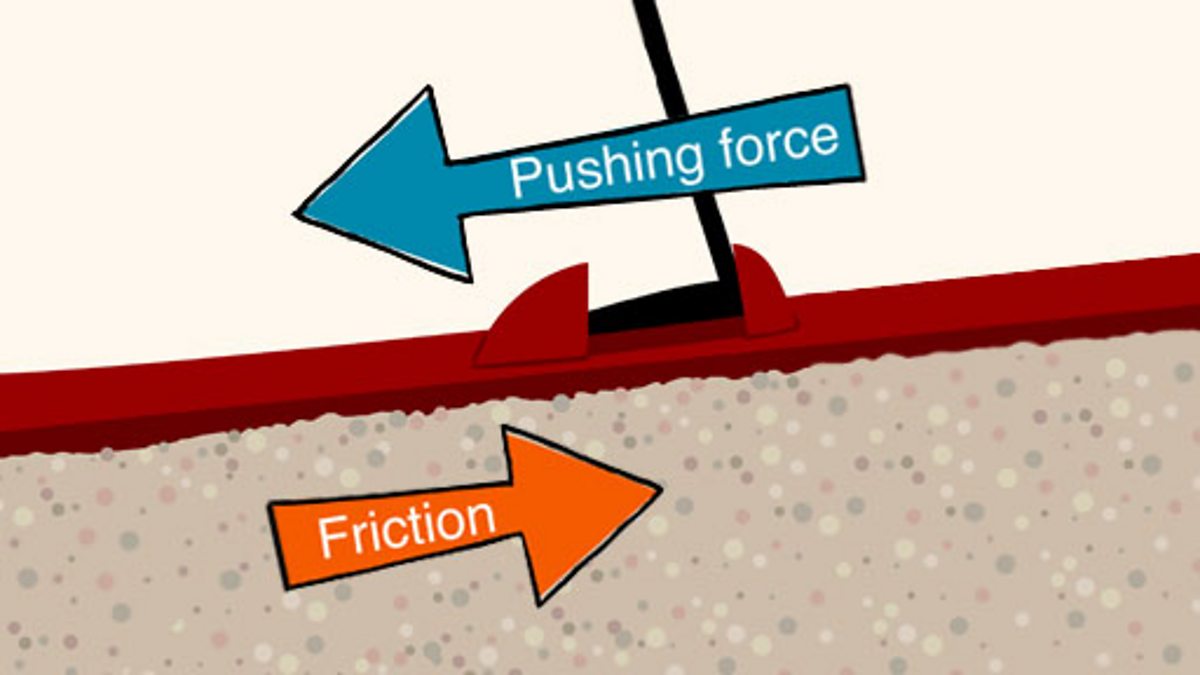

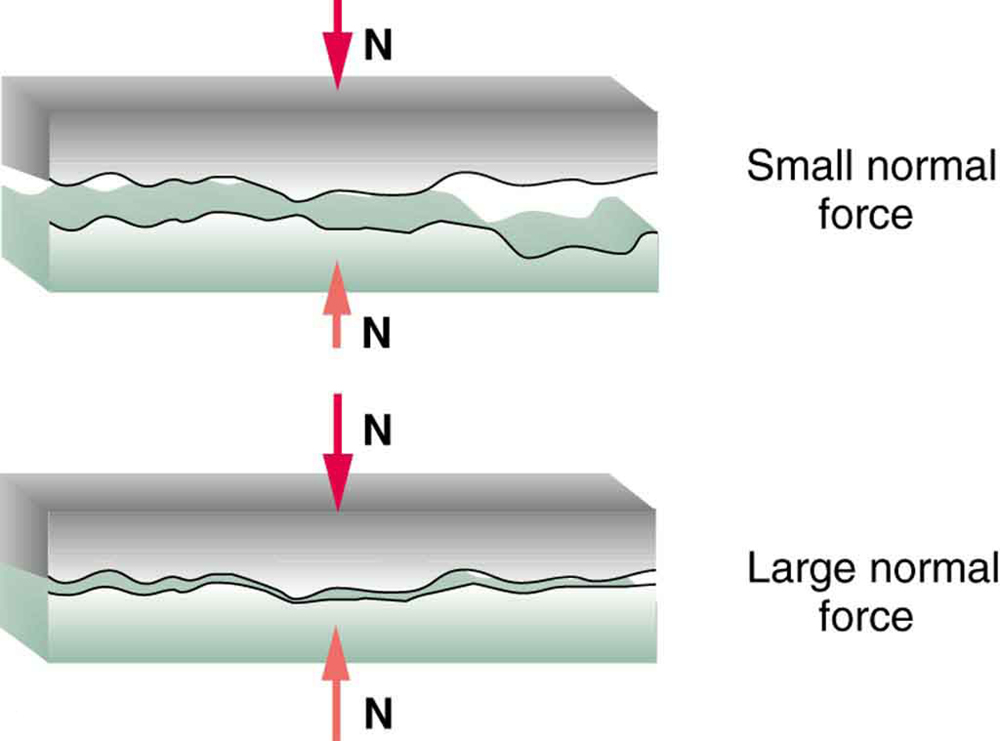

Essentially, friction is a manifestation of electromagnetic interactions between the atoms of two surfaces in contact. The roughness of surfaces, even those that appear smooth to the naked eye, creates microscopic hills and valleys. When these surfaces come into contact, these irregularities interlock, leading to resistance. This interlocking is influenced by the materials involved and the normal force pressing them together. The greater the normal force, the more tightly the surfaces are pressed together, and the greater the frictional resistance.

Furthermore, consider that friction always opposes motion. It's a resistive force, not an active one. It doesn't initiate movement; it hinders it. This reactive nature is a key characteristic that sets it apart from fundamental forces. It's the ultimate party pooper of motion, always there to slow things down or bring them to a halt. It's the reason your car eventually stops rolling if you take your foot off the gas.

The Microscopic Dance: Electromagnetic Interactions and Surface Irregularities

Delving into the Atomic Level of Friction

To truly grasp the essence of friction, we must venture into the microscopic world. Surfaces, even those polished to a mirror-like finish, possess irregularities at the atomic level. These imperfections, though minuscule, play a pivotal role in generating friction. When two surfaces come into contact, these irregularities interlock, creating resistance to motion. The strength of this interlocking depends on the nature of the materials and the applied normal force.

The electromagnetic forces between atoms and molecules are the primary drivers of this interaction. Atoms in close proximity experience attractive and repulsive forces due to the distribution of their electrons. These forces, when summed across the vast number of atoms in contact, manifest as the macroscopic force of friction. This is why different materials exhibit different coefficients of friction; their atomic structures and electron distributions vary, leading to different strengths of interaction.

Imagine two pieces of sandpaper rubbing against each other. The rougher the sandpaper, the more significant the interlocking of irregularities, and thus, the greater the friction. Conversely, smoother surfaces exhibit less interlocking and lower friction. This is why ice, with its relatively smooth surface, allows objects to slide with minimal resistance. The atomic interactions are diminished.

The normal force, the force pressing the surfaces together, also plays a crucial role. A greater normal force increases the contact area and the interlocking of irregularities, leading to higher friction. This is why pushing down harder on a box makes it more difficult to slide. It's not magic, it's just the atoms doing their thing.

Static vs. Kinetic Friction: Two Sides of the Same Reactive Coin

Understanding the Different Types of Frictional Resistance

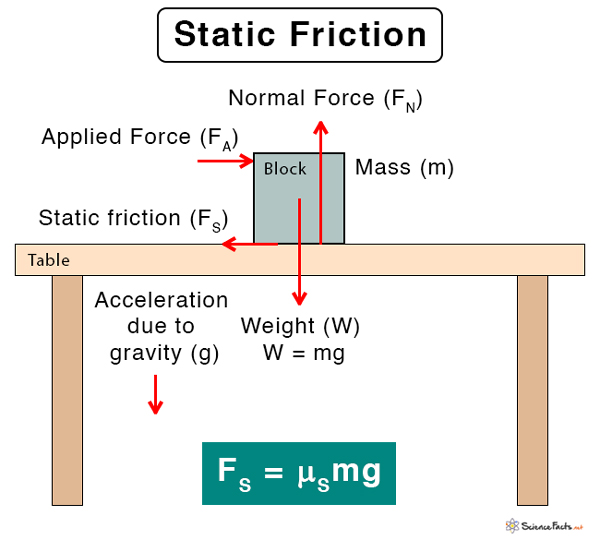

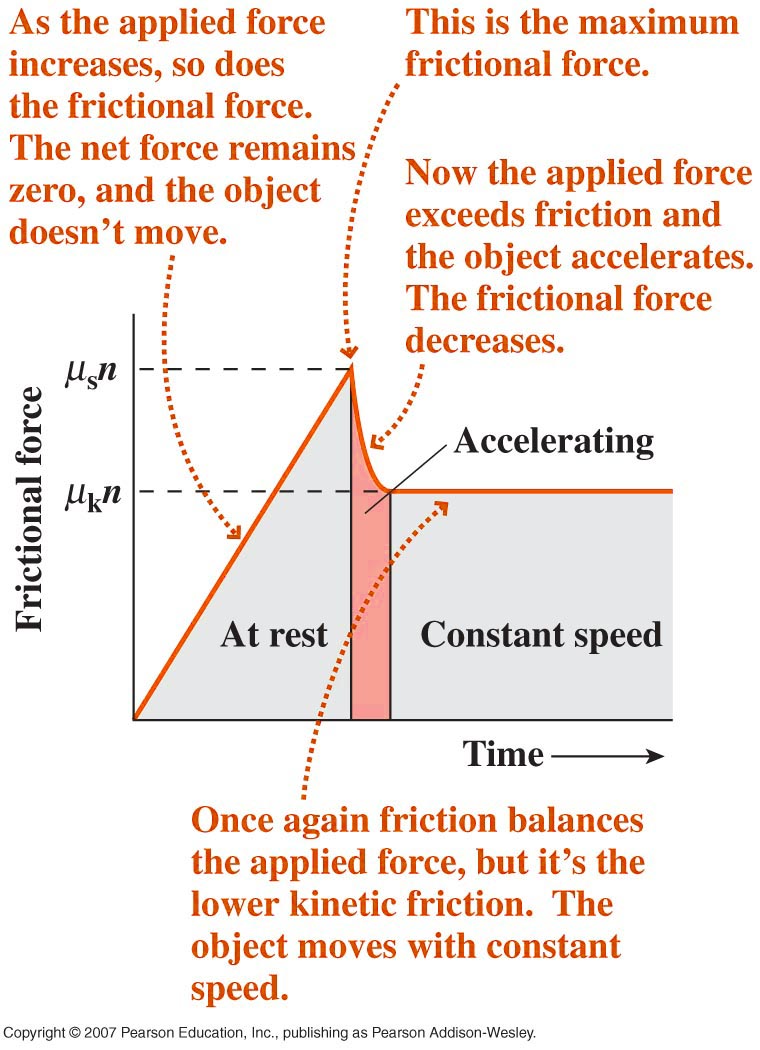

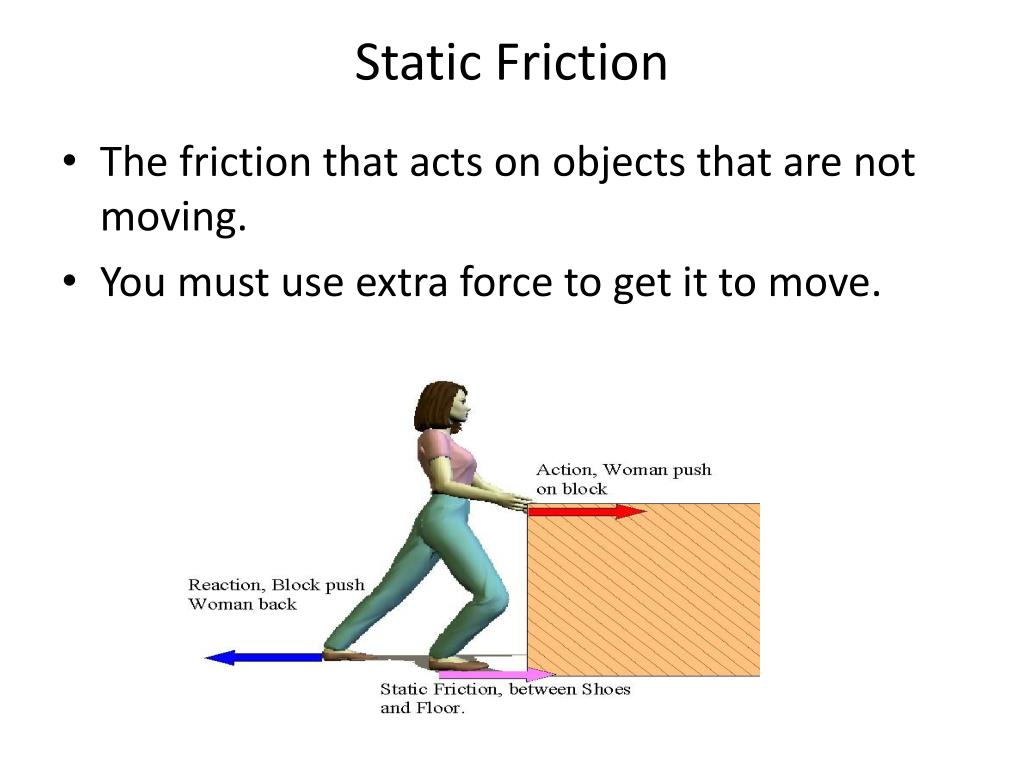

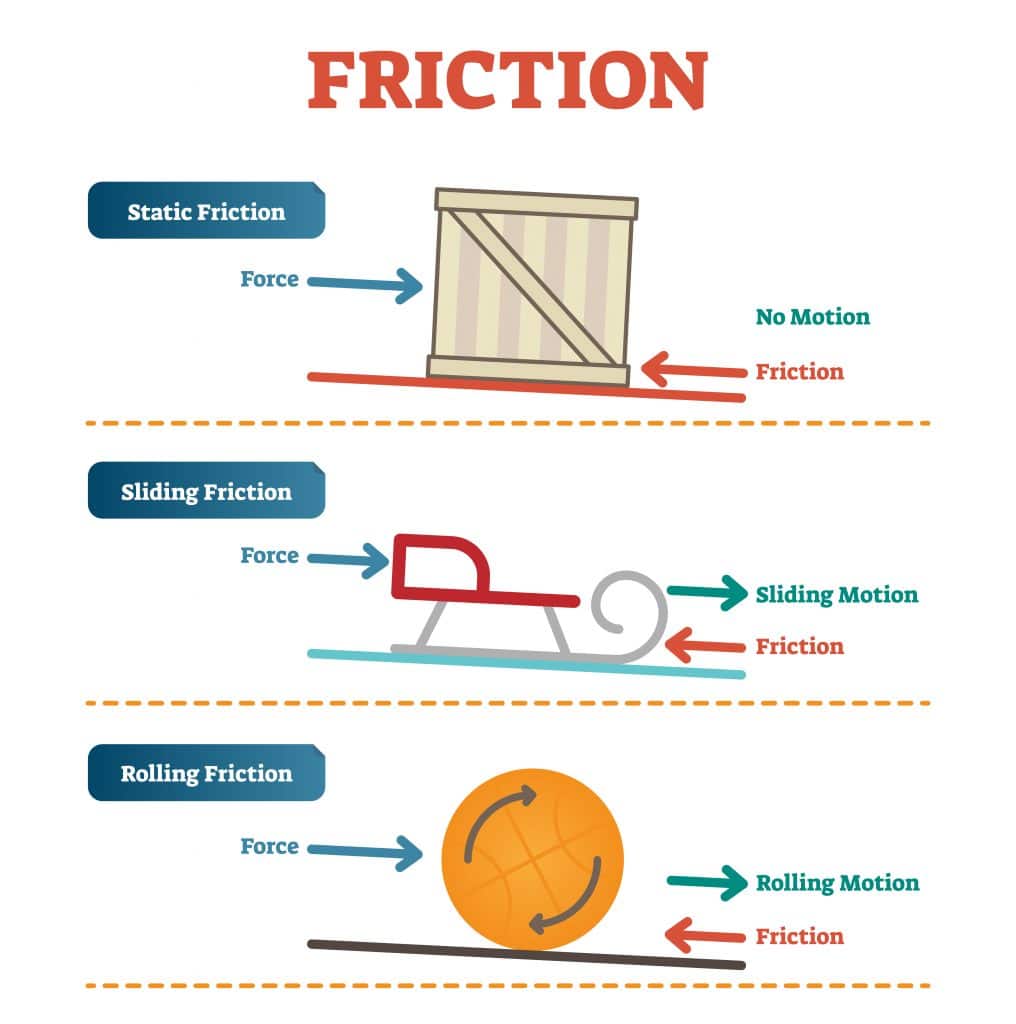

Friction manifests in two primary forms: static and kinetic. Static friction is the force that prevents an object from moving when a force is applied. It's the initial resistance you encounter when trying to push a heavy object. Kinetic friction, on the other hand, is the force that opposes the motion of an object already in motion. It's the resistance you feel while pushing that object across the floor.

Static friction is generally greater than kinetic friction. This is because the irregularities between surfaces have more time to interlock when the object is stationary. Once the object starts moving, the irregularities have less time to fully engage, resulting in lower resistance. This is why it takes more force to start pushing a box than to keep it moving. It's like overcoming an initial hurdle, and then it gets a bit easier.

Both static and kinetic friction are reactionary forces. They arise in response to applied forces and oppose motion. They are not fundamental forces in themselves but rather manifestations of electromagnetic interactions at the microscopic level. They are the ultimate "no" vote in the motion election. They simply react to what is already happening.

The coefficient of friction, a dimensionless quantity, quantifies the strength of frictional resistance. It depends on the materials in contact and the nature of their surfaces. It's a handy number to have when you're trying to figure out how much force you need to move something. It's also why you need different tires for different weather conditions.

The Normal Force and its Influence on Frictional Resistance

How Applied Pressure Affects Friction

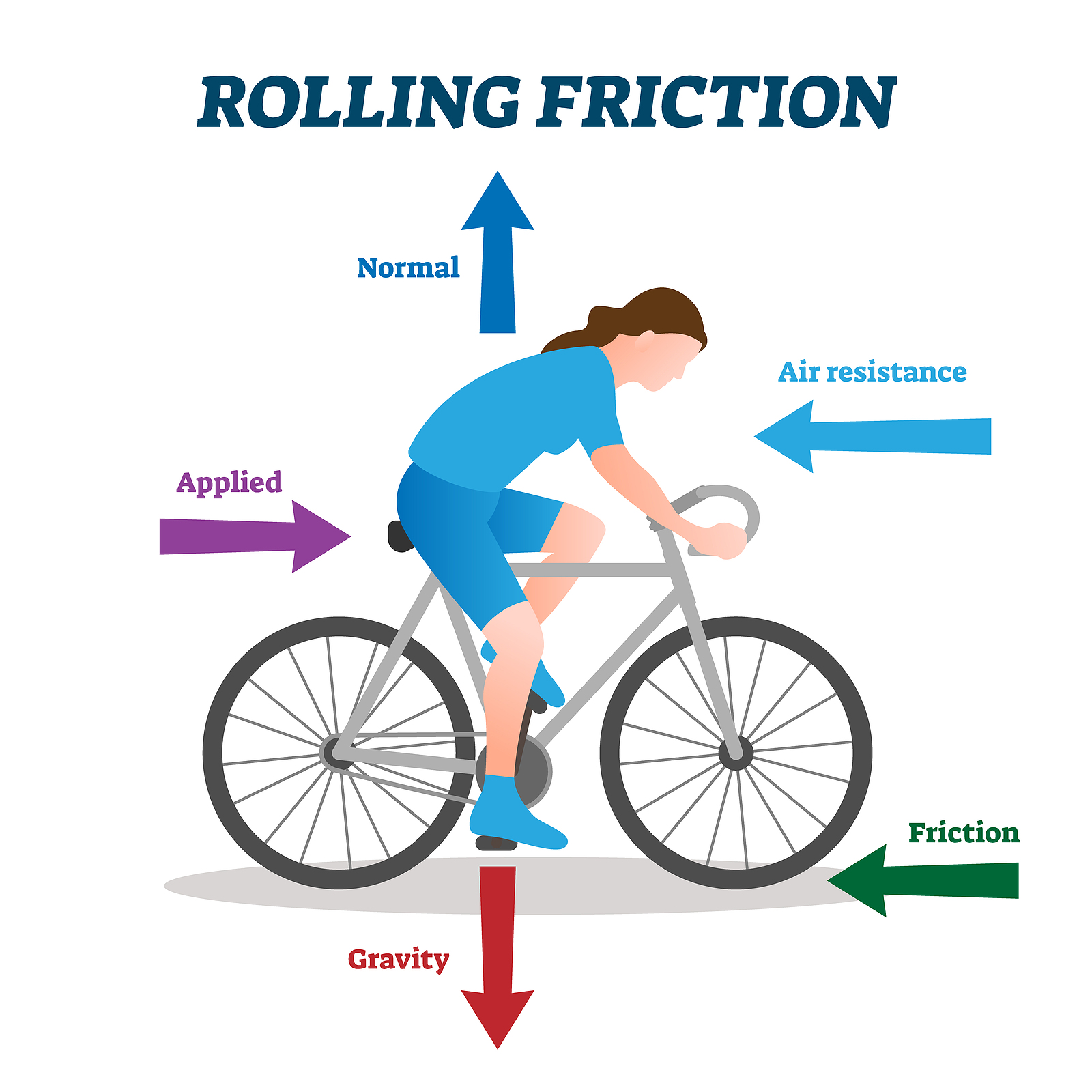

The normal force, the force perpendicular to the surfaces in contact, significantly influences frictional resistance. A greater normal force increases the contact area and the interlocking of irregularities, leading to higher friction. This principle is evident in everyday scenarios, such as pushing a heavy box versus a light one. The heavier box exerts a greater normal force, resulting in more friction.

Consider a car tire on a road. The weight of the car exerts a normal force on the tire, pressing it against the road surface. This normal force, in conjunction with the tire's material and the road's surface, determines the level of friction. In icy conditions, the normal force remains the same, but the coefficient of friction decreases, resulting in reduced traction. This is why winter tires are designed with materials and treads that increase the coefficient of friction, even in slippery conditions.

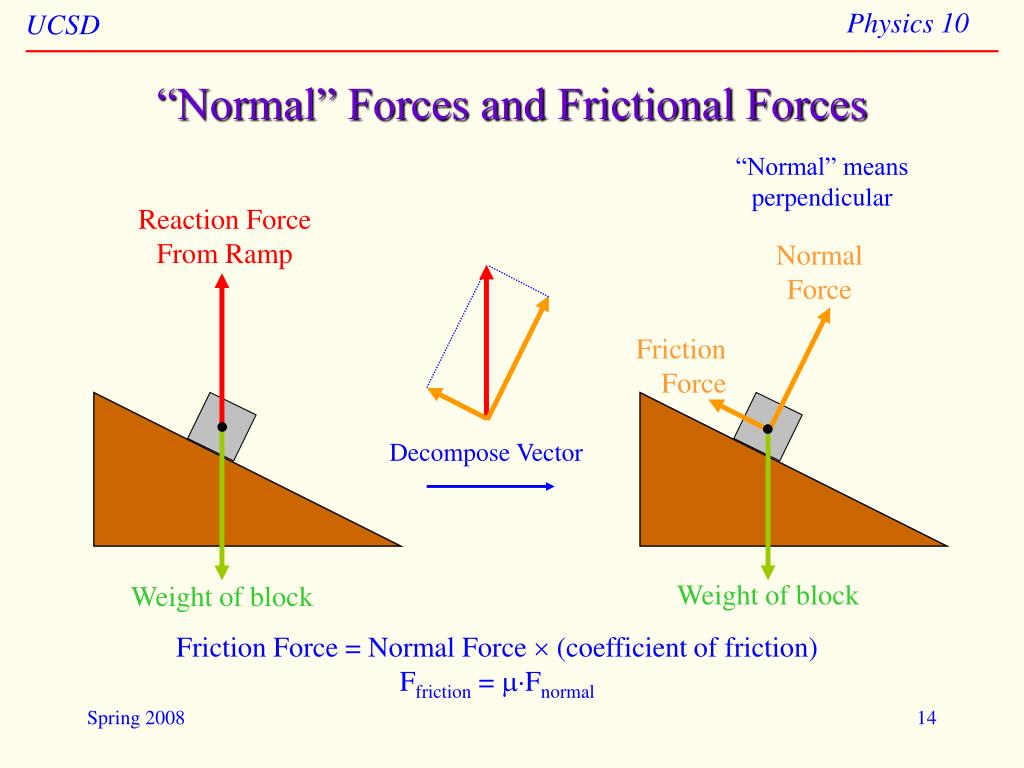

The relationship between normal force and friction is often expressed through the equation Ff = μFn, where Ff is the frictional force, μ is the coefficient of friction, and Fn is the normal force. This equation highlights the direct proportionality between normal force and frictional resistance. It's a simple equation, but it explains a lot about why things slide or don't slide.

It's important to remember that the normal force is not always equal to the weight of an object. On an inclined plane, for example, the normal force is a component of the weight, perpendicular to the surface. This variation in normal force leads to corresponding changes in frictional resistance. It's all about the angle, literally.

Friction in Everyday Life: Beyond the Textbook

Practical Applications and Real-World Examples

Friction plays a crucial role in numerous everyday phenomena. Walking, for instance, relies on static friction between our shoes and the ground. Without it, we would slip and slide with every step. The design of tires, brakes, and clutches in vehicles is heavily influenced by friction considerations. Engineers carefully select materials and design surfaces to optimize frictional forces for specific applications.

Consider the humble matchstick. Striking a match involves overcoming static friction to generate heat, which ignites the match head. This simple act relies on the controlled release of frictional energy. The design of screws and nails also leverages friction to hold objects together. The threads of a screw create a large contact area, increasing frictional resistance and preventing loosening.

Even the act of writing with a pencil relies on friction. The graphite in the pencil lead is deposited onto the paper due to frictional forces. The roughness of the paper surface allows the graphite to adhere, leaving a visible mark. Without friction, we wouldn't be able to write or draw.

Friction also plays a vital role in natural phenomena. The movement of tectonic plates, for example, is influenced by frictional forces at their boundaries. These forces can build up over time, eventually leading to earthquakes when they are suddenly released. It's a powerful reminder that friction is not just a classroom concept, but a fundamental force shaping our world.

FAQ: Friction Decoded

Answering Common Questions About Frictional Forces

Q: Is friction always a bad thing?

A: Not at all! While friction can cause wear and tear and reduce efficiency, it's also essential for many everyday activities, such as walking, driving, and writing. It's all about context.

Q: Why does ice have low friction?

A: Ice has a relatively smooth surface at a microscopic level, reducing the interlocking of irregularities between surfaces. Additionally, a thin layer of water can form on the surface due to pressure, further reducing friction.

Q: Can friction create heat?

A: Absolutely! Friction converts kinetic energy into thermal energy, which manifests as heat. This is why rubbing your hands together makes them warm.